Sonata in D major for two pianos, MWV S 1

Klavierstück [Sonata movement] in G minor for two pianos, MWV S 2

Fantasie in D minor for piano four hands, MWV T 1

Duetto [Allegro brillante] in A major for piano four hands op. 92, MWV T 4

Andante con Variazioni in B fl at major for piano four hands op. 83a, MWV U 159

Incidental music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream op. 61, MWV M 13

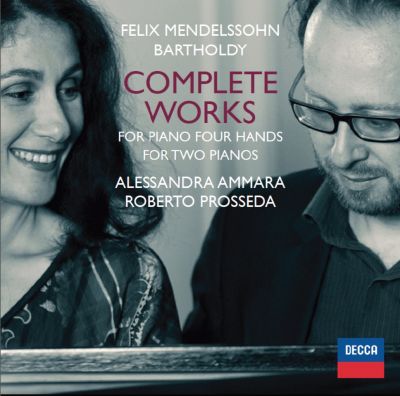

ALESSANDRA AMMARA and ROBERTO PROSSEDA, piano

Recorded at Fazioli Concert Hall, Sacile, Italy, Jun 24-26, 2015.

Sound engineer: Matteo Costa

Reviews:

Is there another single-disc recording of all five of the complete original pieces composed by Mendelssohn for piano duet and two pianos? If so, I doubt if it’s as good as this with Roberto Prosseda, tireless champion of the composer, joined here by his wife Alessandra Ammara.

If in the Sonata in D major and the single sonata movement (aka Klavierstück) in G minor – both for two pianos – we do not hear the distinctive voice of the composer, then we should surely gasp in admiration that such music was composed by an 11-year-old. The sonata is clearly modelled on Mozart’s great K448 Sonata (in the same key) just as the Fantaisie in D minor for piano four hands (composed 1824 but published only in 2009) shares some characteristics (though not as obvious) with the Fantasy in D minor, K397; it has four linked sections lasting 13'19", making it, as Prosseda rightly asserts in the booklet, ‘one of the most interesting rediscoveries of Mendelssohn’s works that have been made in recent years’. In the next two pieces, the Duetto and Andante con variazioni (adapted from the Variations, Op 83, for solo piano) from 1840 and 1844 respectively, we have the echt Mendelssohn, glorious melodies and brilliant writing despatched con amore e con spirito by Ammara and Prosseda.

The disc ends with the composer’s own and rarely heard piano-duet arrangement of the incidental music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the six purely instrumental movements familiar from the orchestral suite. Good programming by the duo: the Overture (originally a piano duet written when he was just 17) reminds us again of Mendelssohn the youthful genius, while the rest of the suite, composed stylistically seamlessly 16 years later, is contemporaneous with the Andante con variazioni. Altogether a significant and rewarding addition to the Mendelssohn discography.

Jeremy Nicholas, Gramophone, 3/2016.

Le interpretazioni sono, come nel caso di tutta questa integrale, di livello eccelso. Chiarezza, spolverio, eleganza, trasparenza del toccom abbandoni sentimentali e soprattutto senso della misura. Prosseda e la Ammara, infatti, non eccedono nei toni e curano ogni dettaglio fino a conferire a queste pagine una lucentezza ammaliante.

Luca Segalla, Musica, 2/2016 (5 stelle)

Una pubblicazione che va ben al di là dall’essere un complemento all’opera omnia pianistica di Mendelssohn incisa negli scorsi anni da Prosseda, questo cd inciso con la collaborazione della moglie Alessandra Ammara presenta un ventaglio di lavori che affondano le proprie radici nella fanciullezza di un compositore dotato di una facilità e di un estro stupefacenti. Non sappiamo se ammirare di più, in questo disco, il perfetto aplomb, il suono preziosissimo, il gusto eccellente, la conoscenza del linguaggio mendelssohniano dimostrati dai due protagonisti alla tastiera o la bellezza di tutti i numeri eseguiti, ivi compresi i molto mozartiani “compiti in classe” vergati dalla mano di un musicista ancora fanciullo.

Luca Chierici, Classic Voice, 2/2016 (5 stelle, CD del mese)

Liner Notes:

This CD includes all five of the complete original pieces composed by Mendelssohn for piano four hands and for two pianos, as well as the transcription for piano four hands of the incidental music for Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The piano played a central part in Felix Mendelssohn’s work from his very earliest beginnings as a composer: nearly all the examples of his early work written between 1819 and 1821 are for piano. These juvenilia were not published by Mendelssohn (whose op. 1, the Quartet in C minor for piano and strings MWV Q 11, was completed in 1822), and most of them have been rediscovered in the last few decades.

In this context, the Sonata for two pianos in D major MWV S 1 (1820) is of particular interest: it is the first sonata and the first composition in three movements written by Mendelssohn. Despite the inevitable stylistic debts of a composer who was still a youngster and in a formative stage, this sonata already shows the qualities of Mendelssohn’s poetics: the felicitous melodic invention is combined here with refined contrapuntal writing, sustained throughout by a brilliant rhythmic beat. It was probably a task that was assigned to the young Mendelssohn by his composition teacher, Karl Zelter, and the references to Mozart’s Sonata K 448 for two pianos (also, incidentally, in D major) are so explicit as to make one think of a deliberate stylistic exercise: a kind of paraphrase of Mozart’s sonata in a more succinct virtuoso form.

The other piece that Mendelssohn composed for two pianos is the Klavierstück in G minor MWV S 2, which also dates from 1820. Here, too, we find references to the expressive ambience of the late Mozart and particularly to the Symphony in G minor K 550, but with greater harmonic originality than in the preceding sonata. The form is that of the first movement of a sonata, and it is a pity that Mendelssohn did not compose the other movements, which could have given us an even more interesting second sonata for two pianos.

Mendelssohn composed three original works for piano four hands, all published posthumously. For the sake of completeness we must also mention the Andante in G minor MWV T 3, which is not included in this CD as it is an incomplete fragment.

In the early nineteenth century there was a great deal of music for piano four hands: mostly easy compositions intended to be performed by amateur pianists in a domestic setting. This also explains the great quantity of transcriptions of symphonic and operatic works, at a time when the piano was still fulfilling the function of reproducing music, a function now performed by the radio or by CD players. However, Mendelssohn’s works are exceptions: both in the original pieces for piano four hands and in his transcriptions from symphonic works the piano writing is always very bold and full of virtuosity and undoubtedly intended for professional pianists. Moreover, Felix was himself a keyboard virtuoso, as was his sister Fanny, and the two of them certainly often played together as a duo during the years of their youth.

The Fantasie in D minor for piano four hands MWV T 1 was composed by Mendelssohn in 1824. The manuscript, now preserved in the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin, was not published until 2009, when the first edition appeared (Raitrade RTC 3176). Unlike the autographs of other youthful works by Mendelssohn, in this case there are also many indications of dynamics and articulation, evidence of the care with which the composer polished the details of this Fantasie. The structure of the work consists of four interconnected sections: a solemn introduction in D minor, Adagio, once again full of Mozartian suggestions (one cannot help thinking of the Requiem in D minor K 626), leading to an Allegro, also in D minor, in sonata form. This is followed by another Adagio, in B flat major and in ABA form, with a bel canto expressiveness. A gradual accelerando brings us to the final Allegro molto, in D major. Here the writing becomes even more pyrotechnic, and the second theme of the preceding Allegro reappears, a sign of the formal refinement of this Fantasie, which is one of the most interesting rediscoveries of Mendelssohn’s works that have been made in recent years.

The other two original pieces for piano four hands date from the years of his maturity. The Duetto MWV T 4 was composed in 1841 and exists in two versions: the better-known one, based on the manuscript preserved in the Biblioteka Jagiellońska in Kraków (23 March 1841), consists of a single movement and was published in 1875 by Breitkopf, edited by Julius Rietz, as Allegro brillante op. 92. However, the complete version of the Duetto also includes an introductory Andante, present in the manuscript that is kept in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, dated 26 March 1841 (three days after the other one). The present recording is based on this version, first published by Henle (HN 324) in 1994. The work adopts the structure of a kind of diptych in which the initial Andante, with two melodic lines that alternate as in Mendelssohn’s vocal duets, provides a suitable preparation for the Allegro assai vivace that follows, with a bright, sparkling virtuosity.

The Andante con Variazioni op. 83a was composed in 1844 and was derived from the similarly titled op. 83, MWV U 159, for piano solo. However, the version for four hands is not a mere transcription but really is “another way”, setting out from the same theme and gradually diverging from the version for piano solo with the introduction of completely new variations. The presence of two pianists is exploited here to characterise the registers of the piano, and often the theme passes from one pianist to the other, giving rise to interesting expressive differences.

Apart from the original works already mentioned, Mendelssohn made various transcriptions for piano four hands of symphonic works written by himself (including the Octet and the First Symphony) or by other composers (Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony and Haydn’s Seasons – but both only partially transcribed). The most fascinating and successful transcription is undoubtedly that of the incidental music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, presented here in the original version published by Breitkopf in 2001 (SON 407). The present recording includes the purely instrumental movements (Overture, Scherzo, Intermezzo, Nocturne and Wedding March) that are often played as a unified suite also in the orchestral version. For obvious reasons, the parts including the choir and the links and fragments have no raison d’être outside the context of a theatrical performance. Mendelssohn succeeded in capturing the most magical and mysterious qualities of the enchantment of the night in Shakespeare’s play. His piano transcription preserves the brilliant solutions of timbre in the orchestral arrangement, making the perception of the musical design even more transparent.

Roberto Prosseda